A personal perspective on why I love this novel.

“Mother died today. Or maybe yesterday. I don’t know.” This is the opening line of The Stranger, spoken by its protagonist, Meursault. They are perhaps Camus’ best known words. This idea had preoccupied him since he started writing. He wrote of the funeral of his brutal grandmother, recalling “Only on the day of the funeral, because of the general outburst of tears, did he weep, but he was afraid of being insincere and telling lies in the presence of death.” In another story, he wrote of his half-mute mother who showed him no affection. She was “a poor old woman whose fate moves men to tears.” But his relationship with her was different: “It’s true, he never talked much to her. But did he ever need to? When one keeps quiet, the situation becomes clear. He is her son, she is his mother.”

We will never know what Camus thought of his mother but what really matters is that he used this image to introduce his readers to a strange new world. And it is a most absurd world. Even though Meursault is charged with killing a man, he is told by the court: “any man who was morally responsible for his mother’s death thereby cut himself off from the society of men to no lesser extent than one who raised a murderous hand against the author of his days.”

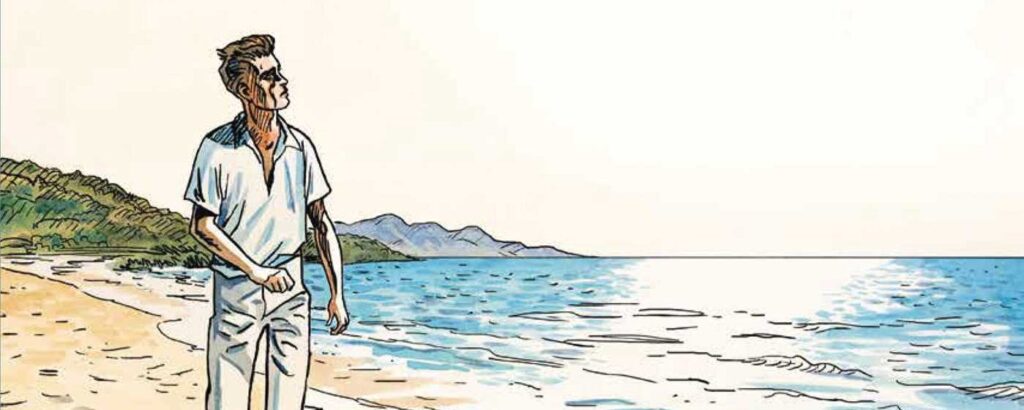

Meursault is caught up in a cosmic tragedy. He is living a sensual life until one day, while out swimming, time stops still at midday and the sky “seemed to be splitting from end to end and raining down sheets of flame.” He commits a crime by shooting a man and says, “I realised that I’d destroyed the balance of the day and the perfect silence of this beach where I’d been happy.” The righteousness of the gods will fall upon him, wielded by magistrates who seek his beheading. And yet, confined to his prison cell, he learns to be free by living within his limits. And he remains human. When the chaplain tells him that his crime is a sin, Meursault reflects to himself. “He seemed so certain of everything, didn’t he? And yet none of his certainties was worth one hair of a woman’s head.” Camus mentions the sun-filled sky seventeen times in this short novel, and only on the last page does Meursault look and see stars and that is when he first opens himself to the benign indifference of the universe and face his imminent death.

Camus loved Fyodor’s Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground and one can think of the French-Algerian, Meursault, as being Camus’ antithesis of the anti-hero from snowy St Petersburg. The man from underground overthinks, is burdened by shame and vanity and hides himself from the world. He hates to be judged and is quick to take offence and to justify himself. Meursault is the complete opposite. And this makes sense when one considers that Dostoevsky made his absurd hero as abject as possible, so that he would be ready to confess his sins and accept the love of God. Camus, on the other hand, gave his absurd hero a godlike ability not to lie and for that he is condemned to death. Camus speaks to his audience directly when Meursault says, “I am like everyone else, exactly like everyone else.”

The Stranger was recognised as a classic when it was published in 1942 and would go on to be one of the most popular books in France and read by students around the world more than 80 years later. Complemented by his essay, The Myth of Sisyphus and his play, Caligula, it is a supreme evocation of an absurd world.